Debugging SRE #2: Pager Burnout

Table of Contents

It goes without saying that even the most disciplined SRE functions eventually experience pager burnout. Over time, I’ve found that the reasons can be condensed down to 4 main reasons:

- Lack of pager review

- Undersized teams

- Incompatible on-call shift length

- Inadequate on-call compensation

#

Pager Review

##

Treat a Page Like a Page

The most mindblowing thing to me was seeing teams use Slack notifications as a pager alert.

Repeat after me:

A Slack message is NOT a page.

Feeding all alerts into a Slack channel, or even multiple Slack channels, will conflate all urgency levels for alerts. And because a Slack notification just beeps on the phone, on-callers end up glued to their phone 24/7, never able to detach from work even after business hours.

There is a better way to do this. All alerts should be broadly categorised into:

- Page (Urgent)

- Send an alert requiring immediate attention and acknowledgement. This can be an SMS, a phone call, or an app like PagerDuty that sends a push notification which overrides on your phone alarm settings.

- Notify (Not Urgent)

- Send a Slack notification, file a Jira ticket, send an email.

Just by doing this, teams can chuck non-urgent signals into a queue to work on during office hours. On-call responders can tune out from the Slack channels to only respond when paged.

##

Tweak Alert Thresholds

One of the first things I noticed after joining my current team was the sheer amount of alert noise going on in the Slack channels. A major part of the noise was clearly due to overly sensitive alerting thresholds and low priority signals:

- 1 pod in a service had a 2 minute CPU utilisation above 50%.

- Increased 4XX errors not within rollout periods.

- Batch job taking longer than usual to run.

- P99 latency above 500ms for 1 minute.

Are these signals important? It depends on the context, but the easiest way to ascertain is to ask the question: “What’s the worst that can happen if this issue is handled next business day?”

Every team should set up fixed intervals for pager hygiene check-ins. Get every on-call responder together, list and group all pager alerts, then review with the following chart:

graph TD;

A[Pager Alert] --> B{Would ignoring this alert cause noticeable user impact within the next few hours?}

B -->|Yes| C[Keep as Page]

B -->|No| D{Options}

D -->|Downgrade| E[Downgrade to Notification]

D -->|Tweak| F[Tweak Threshold]

#

Size Your Team Correctly

When asked what the correct size of a SRE team (or on-call response roster) should be, I usually say 6 is minimum, 8 is a comfortable N+2. Coincidentally, the number 8 is also recommended by the Google SRE Book.

While the book failed to provide any data based rationale for the recommended number, I could try to fill in the reasoning here based on my own anecdotal experience (I know, it’s a sample size of 1 so pinch of salt).

There are a few considerations when staffing an on-call roster:

- Scope of work - Is it purely on-call response and operations? Or is it on-call + ops + project work?

- Fatigue management - How many pages does the average on-caller get per shift? How long ago was the previous shift?

- Familiarity - Are the shifts close enough to retain response familiarity? Are the shifts far enough that responders get to rest their mind and get project work done?

- Length of shifts - Are the shifts long enough to retain context for alert response? Are the shifts short enough that the responder doesn’t dread each shift?

Personally, I have found that after a week-long shift, I would take about 5-6 weeks to recover enough to psyche myself up for the next shift. This translates to a minimum requirement of 6 people on the on-call roster. In order to ensure that the service would run smoothly even during the festive season where multiple people would be going on vacation, we provision N+2 for 8 people on rotation.

This number may be able to be reduced if the responders are full-time on-call responders and operations. But given that most small to medium tech companies expect their development team to do on-call, the recommendation of 8 people would definitely apply.

##

Anecdote Time

I joined YouTube Video Processing SRE in 2021 and found out that a large chunk of the Zürich team had just transferred out. The on-call rotation, inclusive of me, had dropped to just 5 people. Hiring became my manager’s top priority, while also asking for volunteers from other SRE teams to double hat on our roster. Any time one of us had to go on a long vacation, I would dread the on-call shifts as I could get almost nothing done for my projects. The entire team had to do our own bin packing of on-call shifts as we were all maxing out the quarterly cap of 80h on-call. After which we no longer get paid for it. Things only mellowed out after we hired 2 more SREs onto the team.

When I first brought up this number, the immediate reaction by several managers was that an 8-person team was too big and bloated. They seem to conflate project work and running operations. Because regardless of workload, you need to provide enough space between shifts for a reliable on-call roster. Furthermore, unlike YouTube where I had 12h shifts before handing off to the San Bruno team, my current vocation is in a single region service. The shifts are 24/7, there is no mental rest for an entire week.

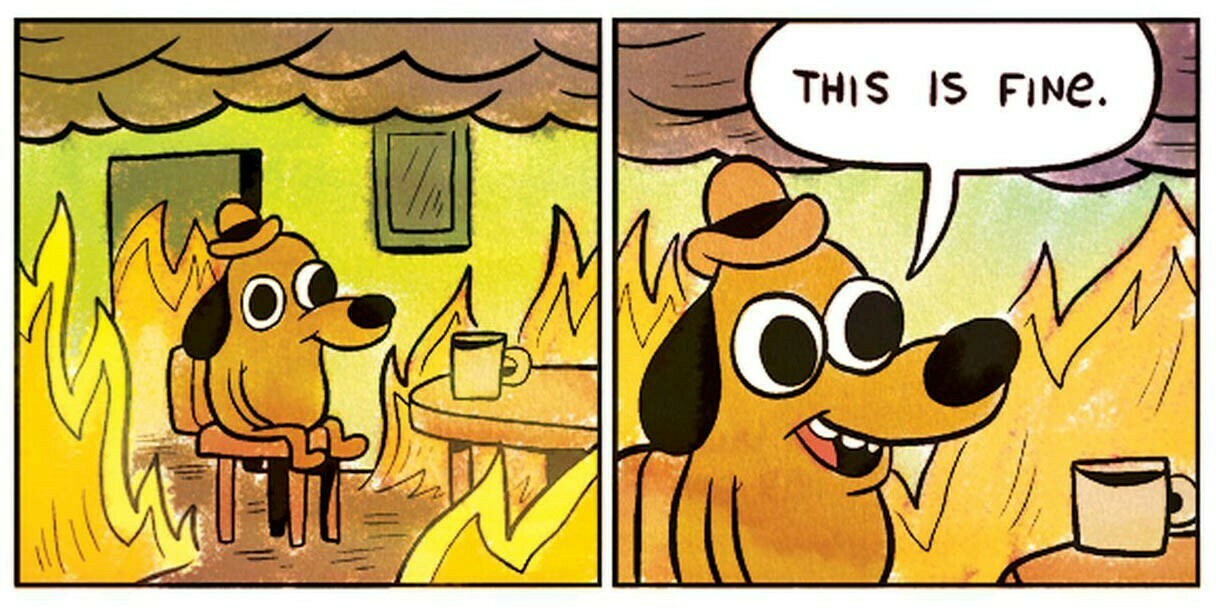

Too many people discount the mental abuse one goes through having to go to bed every night knowing that there is a chance they’d be woken up at 3am. Weekends involve staying at home most of the time because lugging a laptop around is such a chore. Hiking is a production readiness hazard, since you might lose reception on your phone and miss a page.

There is no mental sanctuary for the entirety of the on-call period. There is no escape for the unrelated spouse who gets woken up in a panic, slapping the shit out of the on-caller about the system burning down. My wife still shudders to this day when a specific Android ringtone starts playing.

Do the right thing, min 6 best 8.

#

Play Around with Shift Lengths

Here’s a list of on-call intervals that my various teams have tried and tested, along with what I think of it:

- 2 weeks

- Pure torture. No escape for 2 whole weeks. 2 whole weekends burnt. Zero project work done.

- 1 week

- It’s the default. It’s manageable, but I was always looking forward to the end of the suffering.

- 1 day

- It’s nice that I can hand off and not think about on-call for a week, but I lose contiguous project work weeks. The shift is also not long enough for me to do any meaningful follow-ups on the system tickets before handing off to the next on-caller. The system tickets just start to pile up.

- Half week (M-T, F-S)

- Optimum. I either get M-T shifts where I lose the majority of the week or I lose the entire TGIF and weekend. Either way I still get something out of the week.

#

Respect Your On-Callers’ Time With Compensation

Google SWEs don’t get paid for on-call under most circumstances. However, Google SREs are paid 67% (tier 1) of their hourly rate for on-call duty outside business hours. This compensation is paid out regardless of whether the responder is paged. This means that if a Google SRE has a weekend on-call shift, they are paid like a full working day. These can either be cashed out or converted to Off-In-Lieu.

Meta on the other hand adopts the method of paying their platform engineers higher on base, but nothing for the on-call shifts.

Most of the other tech companies that I have asked do none of the above. Instead they typically choose 1 of the 3:

- No on-call compensation (OCC). Do your damn job.

- 1:1 Off-in-lieu only if paged, and only if response time stretches over a threshold.

- Manager issues off-in-lieu sparingly based on gut feeling. Maximum X number of days a year.

Here’s why I think Google’s approach makes the most sense.

- Google - On-caller gets paid either way. It is in their best interest to reduce noisy pages and resolve the alert as soon as possible. On-call shifts mean extra pay or time off. So on-callers dread their shifts less.

- Meta - Engineers get paid the same higher base regardless of whether they are on an on-call roster, so why would anyone be happy to go on-call?

- No OCC at all - Competent engineers will just leave, or reject on-call shifts over time, since their personal time isn’t respected.

- 1:1 OIL for threshold - On-callers will just stretch out the response time to hit the threshold.

- Manager gut feel - This is much like no OCC at all.

On-call rosters with no OCC generally suffer high attrition rates, leading to brain drain and lowered MTTR. The responders usually quit or move to teams with no on-call. Do you have a team that seems to be running smoothly with no OCC at all? Let’s check back in after 12 months and see how’s that going.

Respect the personal time of people who are willing to take the mental torture to upkeep the reliability of your services.